In Christ, theology and anthropology meet. Up until Christ, theology had been understood through the lens of anthropology. God, quite often, reflected men; but through Christ, God was clarified. In Jesus, we have the fullest understanding of God, and the rest of scripture should be interpreted through the lens of Jesus.

And what did Jesus show us about God? He taught us to not only love our neighbor but to love our enemies, to turn the other cheek, to go the extra mile, to forgive 70 times 7 (virtually endless to the people of the time). Jesus lived his life as a homeless man, and despite his innocence, allowed himself to be executed, a shameful criminal’s death on a cross where he hung naked on a hill over a busy highway in front of his family, friends and community. While being mocked and tormented to death, he prayed that God would forgive them because they didn’t know what they were doing.

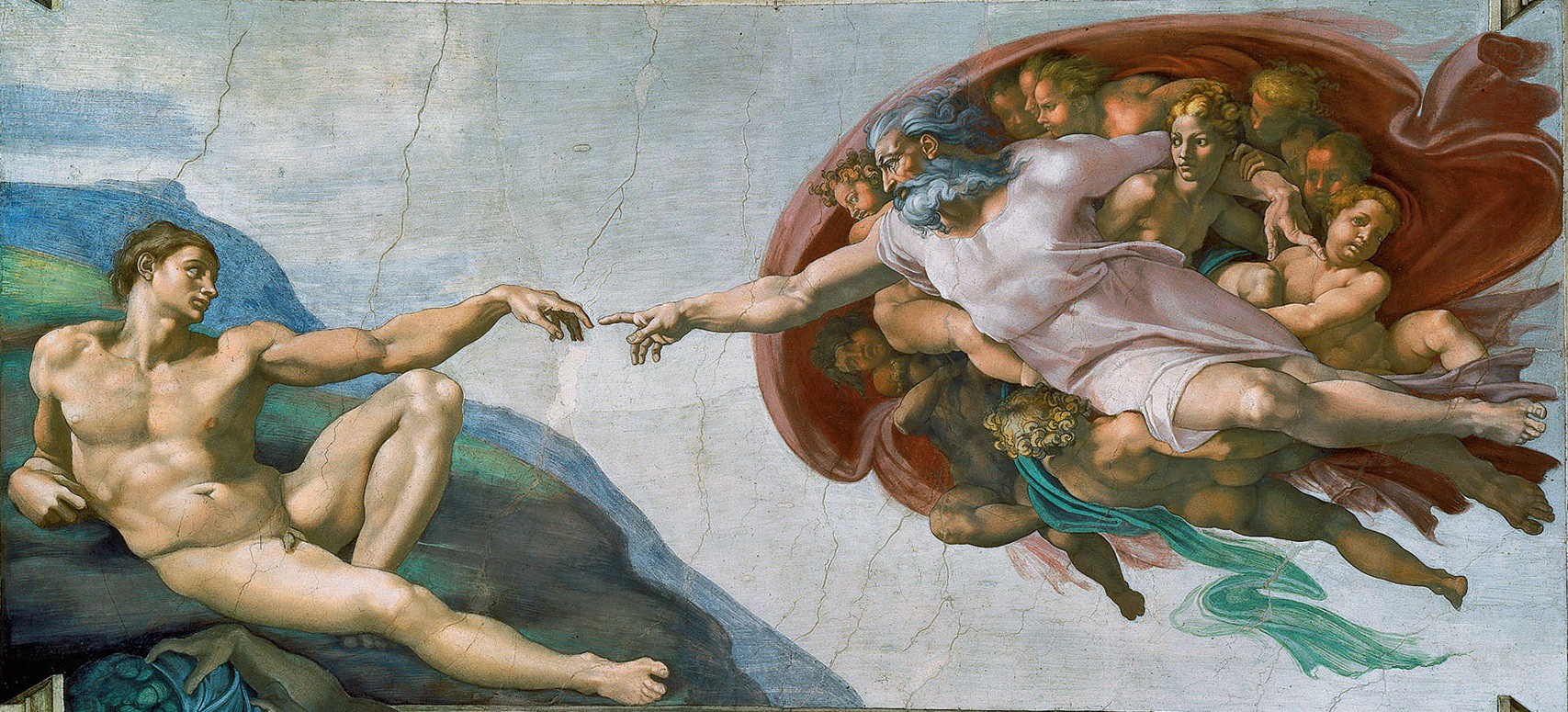

We are also taught throughout the Bible that you become what you worship. Both Jesus and Paul tell us to be “perfect” as our heavenly father is perfect. We are told to be imitators of God. This makes sense in the life of Jesus, but what about God the Father? The God who commanded the Israelites to commit genocide. The God who himself flooded the earth committing geocide. The God who “hated Esau.” The God who killed the first born male of every Egyptian family. What are we to make of this apparent conflict in personalities between God the Father and God the Son?

To make things worse, we have the common teaching on the atonement which says that God sent his son to die in order to appease his own wrath. And why did God have to send Jesus? Because only blood can atone for sins and because God, in his anger and wrath at our sin, is going to send everyone to suffer eternal conscious torment in fiery hell. This doesn’t sound like Jesus.

What if God’s revelation to man is a progression? Just like you can’t teach little kids the complexities of the adult world because their minds aren’t ready to understand it, so humanity was not ready to understand God in his fullness. Which seems painfully obvious if you think about it, since we still aren’t ready for the fullness of God. I think we will spend eternity coming to a fuller understanding of the infinite originator of all creation. Why do you think the Cherubim around the thrown of God are forever falling down on their faces and singing “Holy, Holy, Holy, is the Lord God almighty”? It is because they have just come to understand a new depth or layer to the beautiful greatness of the triune God.

Many will say that progressive revelation is dangerous and that the age of revelation ended with the Apostles or the New Testament writings. But the Bible itself teaches a progression. Abraham didn’t know God like Moses did. It was to Moses that God gave his name “I am that I am.” That was nearly 500 years later. And Moses didn’t have an understanding like Jesus did. Some might argue that Jesus presented the full understanding of God and it ended with him. While in a sense that is true that Jesus is the fullness of revelation, it doesn’t mean that we fully understand what he has revealed yet.

The Apostles obviously didn’t fully understand the resurrection right away. Jesus alluded to the salvation of the Gentiles, but in Acts it took a new revelation for Peter to understand that God could accept unclean uncircumcised Gentiles, and later through Paul that not only would he take them as uncircumcised, but they could stay that way. God supernaturally led Philip to convert a black Ethiopian eunuch that would never have been allowed into Judaism. This continuing revelation happened over the course of 40 years for the Church to fully understand that all people groups were truly part of the new Gospel, and even then, we have struggled with that for 2000 years.

Take slavery for example. The OT all but condoned slavery, and Jesus never condemned it. Paul makes controversial statements, saying there is no difference between slave or freeman (which is revolutionary) and saying to treat slaves as brothers, but there is no outright condemnation of slavery, like we would expect from the Bible. With slavery, you could say that it took us over 1800 years to decidedly say that God would condemn it; now, we would all say that slavery is decidedly anti-Christian.

In light of Jesus’ example of not taking retribution and rather absorbing violence, not only against himself, but in some metaphysical way for all people and all creation, maybe, just maybe, the stories of God’s violence in the Old Testament shouldn’t be taken at face value. Maybe something else is going on that our literal, textbook understanding of the Old Testament is missing. Maybe there is another way that we can still take the OT seriously, but not quite so literally.

Rather than thinking of the OT as a divinely inspired history book that is absolute, we can think of it as the Jewish record of their understanding of God. As Brian McLaren explains it, we have understood the Bible as a Constitutional-type document when really it should be understood as a library of stories about the interaction of God the creator with humanity, seen and understood through the eyes of the Hebrew people, with all of their cultural and contextual baggage (just like we all have). In this view, it is still just as meaningful and is taken just as seriously, not as a textbook on science or as a well-researched history of mankind with primary sources, but for what it was meant to be.

With this literary view, as opposed to a literal view, of the Bible, it allows us to look at it as a cultural and religious document in the historical context it was written.

In Genesis, does God ever command sacrifices? No, except in the case of Abraham and Isaac, but there God provides the sacrifice. Think of what that means in reference to what God does thousands of years later in Jesus.

So, God never commands them to sacrifice, yet they are doing it all over the place starting with Cain and Abel. In these ancient cultures, sacrifice is just assumed. That is how you appease God. So God meets them where they are at culturally and even speaks to them through it. In Exodus, God puts a framework around a sacrificial system, not because that is what he wants or demands, but because that is the religious language that the ancient people spoke. But God puts limits on it, differentiating them from everyone else; for example, they are not to sacrifice their children or any humans. The laws in the Pentateuch all start to make sense now, through this lens of God raising these people up out of the polytheistic, immoral, unhealthy, degrading, and dehumanizing cultures that they came out of and were surrounded by.

Brian McLaren explains how other ancient civilizations had flood stories as well, but the Hebrew flood story differentiates itself as being carried out by a God who cares about justice and mercy. Not by a God who is merely annoyed at how loud people are. Yes, it is still shockingly violent to us today, but to the ancient people it was a revolutionary step toward a loving, purposeful God and away from the frivolous and arbitrary gods of the pagans.

The creation story doesn’t have to be a literal science lesson. Through this literary lens, we learn that creation was no accident, but instead, a loving God purposely and carefully created everything over a period of time, declared it to be good, and created man in his own image. Again, this is a radical change from any other creation story.

So the question is, did God wipe out Sodom and Gomorrah with fire and brimstone? Did he send pestilence and plagues upon the Egyptians and kill all of their first born males? Did God command the Israelites to commit genocide on the Canaanites and to take women and children as slaves from other people groups? Is God violent? Is there an end to his patience? Is God the Father inherently different than His Son? Or could these stories be the result of the history of a people shaped by God but interpreting their circumstances through their own cultural lens?

Instead we find a revolutionary God who works within the confines of man in order for them to understand him but is constantly subverting their normal way of thinking and patiently leading us along, “guiding us in paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.” We see a people in the dark shadow of the world slowly being brought out into the light of a loving, kind, and generous God who meets us where we are at and even speaks to us through our own mythologies.

In the paraphrased words of Peter Enns, if you find it hard to believe that God commanded the Israelites to commit genocide… then don’t. Don’t believe it. Archeologically there is no evidence of this mass genocide or war. Yes, there were Canaanite people, and yes, the Israelites displaced them; yes, there may have been some battles, but nothing on the epic scale indicated in the book of Joshua.

To me this changes everything. We have always been taught that God is love, but there is always been a big “but.” Sure, God is loving and full of mercy and forgiveness, BUT eventually that mercy will run out and his wrath will deal with everyone who doesn’t accept his forgiveness. This creates a serious dichotomy in those who follow him.

As McLaren says, we keep the genocide card in our back pocket. Why? Because our God does, and we become like what we worship. On a smaller scale, it isn’t just genocide, but we are all infected with the violence and coercion that we think God shows, particularly in the OT. But Jesus came and repudiated that understanding of God through both his teaching and his example.

I don’t think most Christians really see God as love, and that is probably our biggest problem and the biggest problem for the world as a whole. I think this needs to change.